Why the USDA Food Pyramid Changed (and What to Do Instead)

By Dr. Priyali Singh, MD

Reviewed by Kenya Bass, PA-C

Published Aug 16, 2025

14 min read

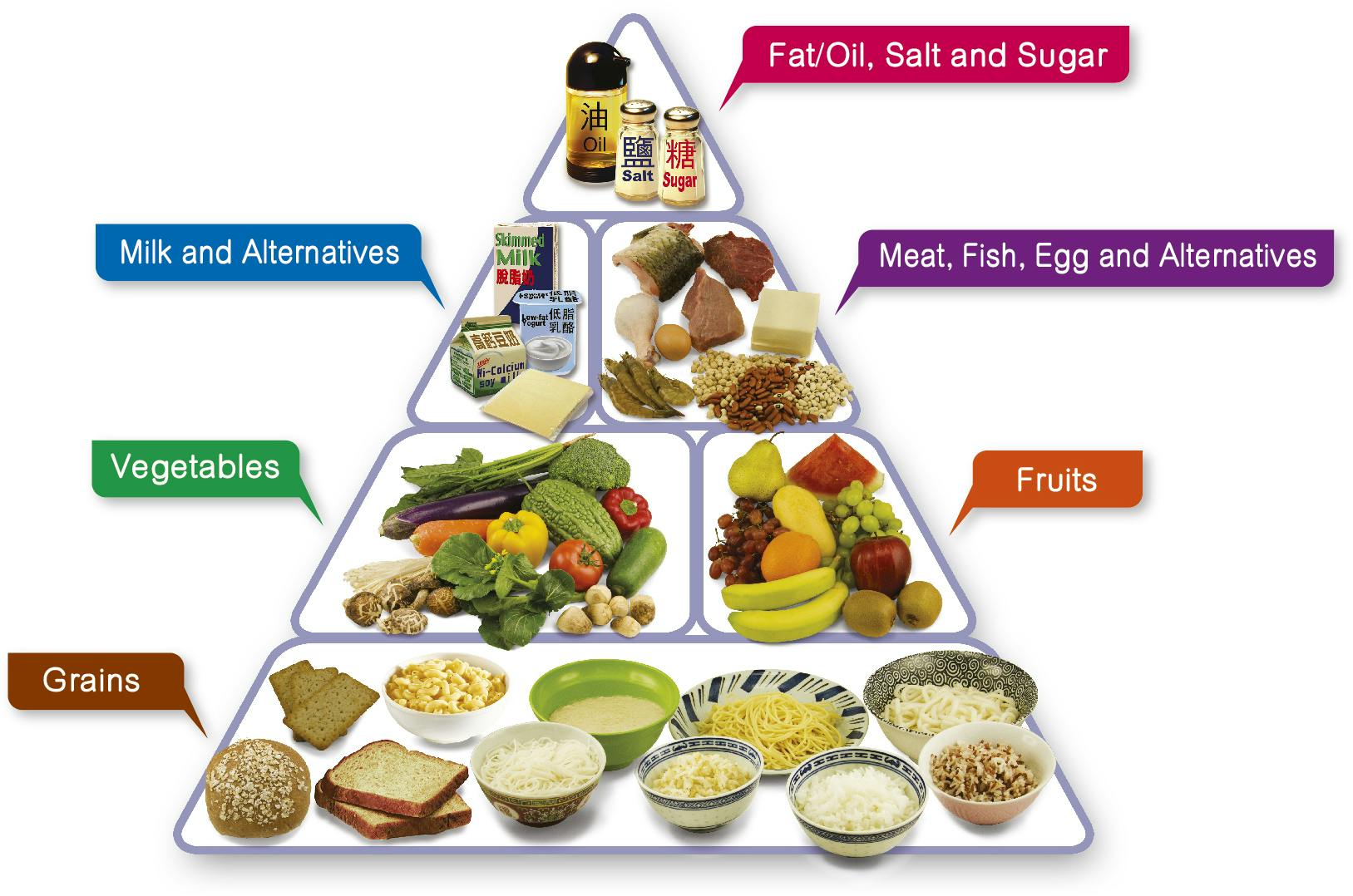

If you grew up in the 1990s, you probably remember the poster that hung in countless classrooms and doctors’ offices: a tall triangle with a wide base of bread, cereal, rice, and pasta, tapering up to a tiny tip for fats and sweets. That Food Guide Pyramid felt authoritative. It was everywhere. It also turned out to be confusing—and in key places, wrong.

In 2011, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) retired the pyramid and launched MyPlate, a simpler plate icon focused on the proportions of foods at a meal rather than rigid numbers of “servings.” MyPlate is the official symbol linked to the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, the federal, science-based advice that’s updated every five years by USDA and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

This article explains why the Food Pyramid changed, the research that drove those changes, the debates that still simmer, and—most importantly—how to use the newer guidance to eat well in daily life. We’ll keep it conversational and practical, but we’ll also reference real studies and include short quotes from experts so you can see how the science evolved.

A quick tour: From pyramid to plate

The first U.S. Food Guide Pyramid launched in 1992. It put grains (6–11 servings/day) at the base and pushed all fats to the stingy top, implying “fat is bad” and “plenty of starch is good.” A revised “MyPyramid” in 2005 added colorful vertical stripes and a little stick figure climbing stairs to hint at exercise, but it offered few specifics people could use. In 2011, USDA replaced the whole thing with MyPlate, a plate divided into vegetables, fruits, grains, and protein, with a side of dairy. The shift was meant to be clearer and more actionable “at a glance.” As then-Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack put it, “The food pyramid is very complicated. It doesn’t give you as much info in a quick glance as the plate does.”(The Nutrition Source, first5sc.org)

Even critics of the government’s graphics welcomed the change in direction. Harvard’s longtime nutrition chair Walter C. Willett, MD, noted at the time: “Clearly MyPlate will be better than MyPyramid… But the most important issues are in the details that are not captured by the icon.” He pointed to differences within food groups—whole vs. refined grains; fish and beans vs. red and processed meats; healthy unsaturated fats vs. saturated and trans fats—as the truly important choices.

Bottom line: The visual changed to be simpler, but the bigger story is that the science evolved—especially around fats, refined carbs, and the risks of ultra-processed foods. Let’s unpack that.

What the science got wrong (and right) in the 1992 pyramid

The 1992 pyramid reflected the best interpretation many experts had at the time: eat less fat to protect the heart, and fill the gap with carbohydrates. That created two problems:

- It lumped all fats together at the top to “use sparingly,” obscuring the health benefits of unsaturated fats (olive oil, nuts, seeds, fish).

- It elevated refined starches (white bread, many cereals, etc.) by placing “bread, cereal, rice, pasta” at the base, without distinguishing whole from refined grains.

Harvard’s Nutrition Source has long summarized these flaws bluntly: the original pyramid “conveyed the wrong dietary advice,” especially by downplaying plant oils and whole grains and by grouping healthy and unhealthy proteins together.(The Nutrition Source)

The fat rethink

Starting in the 2000s, large evidence reviews challenged the simple “fat is bad” storyline. A widely discussed 2010 meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies found no significant association between total saturated fat intake and coronary heart disease, stroke, or overall cardiovascular disease risk when viewed in isolation (though substitution patterns matter).

A 2014 analysis in Annals of Internal Medicine stirred more debate, reporting mixed associations between various fatty acids and coronary risk; it drew sharp criticism for errors and interpretation, underscoring how nuanced this topic is. The take-home wasn’t “fat doesn’t matter,” but rather type and context matter—what you eat instead of saturated fat (e.g., refined carbs vs. polyunsaturated fats) shapes risk.

The more authoritative 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (DGAC) crystallized where the science had landed: dietary cholesterol was “not a nutrient of concern for overconsumption” for the general population, shifting focus away from micromanaging cholesterol and toward dietary patterns and types of fat. (Note: this did not green-light unlimited bacon; it emphasized healthy substitutes and overall patterns.)(Health.gov, PubMed, AJC Online)

In 2020, the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA) reiterated a familiar core: keep saturated fat <10% of calories by replacing it with unsaturated fats, within an overall healthy pattern. The current 2025 DGAC draft executive summary continues to reinforce that substitution, naming butter and red/processed meats as common sources to reduce while replacing with unsaturated fats.(Dietary Guidelines)

Key nuance: If you lower saturated fat but replace it with refined carbs, you don’t gain much. Replace it with polyunsaturated fats (like those from nuts, seeds, and fish) and you do better. That nuance was invisible in the 1992 pyramid.

The carb rethink

The low-fat push inadvertently nudged people toward refined carbs—exactly the foods that can spike blood glucose and insulin, promote hunger sooner, and crowd out nutrient-dense options. MyPlate’s proportional focus on vegetables, fruits, whole grains, and lean proteins reflects the shift to quality over quantity of carbs. The Harvard critiques put it succinctly: the old pyramid’s “overstuffed breadbasket” failed to show that whole grains are better than refined ones.(The Nutrition Source)

RELATED READ: Are Carbs and Sugar the Same? The Truth About Carbohydrates, Glucose, and Your Health

The rise of ultra-processed foods (UPFs)

A pivotal 2019 inpatient randomized trial led by NIH researcher Kevin D. Hall, PhD, found that when adults ate ultra-processed diets ad libitum for two weeks, they consumed about 500 more calories per day and gained weight compared with a minimally processed diet—even when the meals were matched for calories, sugar, fat, and fiber on paper. The effect appears to come from the texture, palatability, speed of eating, and other factors inherent to ultra-processing that drive increased intake. Hall summarized it plainly: the ultra-processed diet caused increased energy intake and weight gain.

UPFs weren’t on the radar in 1992 the way they are now. Today, they’re central to diet-related disease discussions. (Media coverage has followed suit, highlighting the research and policy battles around UPFs and guideline language.)(The New Yorker)

So why did the USDA’s recommendations change?

Short answer: Because evidence accumulated, and the government’s job is to synthesize the preponderance of that evidence every five years into practical, population-level advice—while also managing enormous federal programs like school meals and SNAP that need simple messages to implement. That’s the mandate of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans process.(Dietary Guidelines, Health.gov)

Longer answer: Several currents converged:

- Better evidence on fats and carbs. The field moved from “lower fat at all costs” to “quality matters”—emphasizing unsaturated fats and whole carbs over blanket targets. The 2015 DGAC’s cholesterol statement captured one visible pivot; the 2020–2025 guidelines doubled down on dietary patterns and life-stage specificity.(Health.gov, Dietary Guidelines)

- Recognition of food processing. Controlled feeding studies and a growing observational literature suggest ultra-processing itself—beyond macronutrient breakdowns—can promote over-eating and weight gain. That reinforced guidance to limit highly processed snacks and beverages.(Cell)

- Communication clarity. MyPyramid (2005) was widely criticized as vague and confusing, while MyPlate (2011) is easy to picture at any meal. As Harvard put it, the old visuals “conveyed the wrong dietary advice” and hid crucial distinctions within each food group; MyPlate, while not perfect, was a step toward practical guidance.(The Nutrition Source)

- Policy realities. Guidelines sit at the intersection of science, public health, and politics. Scholars like Marion Nestle, PhD, have documented how industry stakeholders weigh in (sometimes heavily) during guidelines cycles and related food policies. This doesn’t negate the science, but it explains the incremental pace and cautious wording that sometimes frustrate clinicians.(PMC)

What MyPlate actually asks you to do (in plain English)

MyPlate is not a diet plan; it’s a visual ratio for most meals:

- Half your plate: vegetables and fruits (more veg than fruit if you can).

- The other half split between grains (choose whole most of the time) and protein foods (prioritize fish, beans, lentils, tofu, nuts, poultry).

- Include dairy (or fortified alternatives) as needed to meet calcium and vitamin D needs.

That’s it. The power is in customizing those buckets to your preferences, culture, and budget—something the 2020–2025 DGA emphasizes explicitly.(myplate.gov, Dietary Guidelines)

Two small upgrades bring MyPlate closer to where the science is now:

- Favor unsaturated fats (olive/canola/avocado oil, nuts, seeds, fish) and keep saturated fats <10% of calories by replacing, not just removing.

- Make the grain portion mostly whole (brown rice, oats, quinoa, whole-wheat pasta/bread, corn tortillas) and minimize refined, fast-digesting starches.(Dietary Guidelines, The Nutrition Source)

As Willett warned, the icon can’t display those internal “type” choices, but they’re where the health payoff lives. “What type of grain? What sources of proteins? What fats are used to prepare the vegetables and the grains?” he asked when MyPlate launched. You’ll answer those on your plate, not the poster.(Harvard Health)

Clearing up five common myths the pyramid helped create

Myth 1: “All fat is bad.”

No. Unsaturated fats support heart and metabolic health. The goal is to replace saturated fat with unsaturated fats—not to swap fat for refined carbs. That’s why the guidelines keep saturated fat under 10% of calories and highlight polyunsaturated fats as better replacements.(Dietary Guidelines)

Myth 2: “Carbs are good, period.”

Refined carbs (white breads, sugary cereals, pastries) act a lot like sugar in your body. Whole grains and legumes behave differently—more fiber, slower digestion, steadier energy. MyPlate encourages whole grains for exactly that reason.(The Nutrition Source)

Myth 3: “Dietary cholesterol directly drives blood cholesterol.”

For most people, dietary cholesterol is not a major driver of blood cholesterol; that’s why the 2015 DGAC wrote that cholesterol is “not a nutrient of concern for overconsumption.” (Individual responses vary, and overall pattern still matters.)(Health.gov, PubMed)

Myth 4: “If nutrient labels match, foods are equivalent.”

The ultra-processed vs. minimally processed difference matters. In a controlled trial, participants ate more and gained weight on ultra-processed diets despite matched macros and calories served. The texture, speed, and palatability pushed eating beyond fullness.(Cell)

Myth 5: “Guidelines are just politics.”

There’s debate and lobbying, yes; but the process is built on systematic evidence reviews and committee reports. It’s not perfect, but it’s not random. And it keeps evolving as new research emerges.(Health.gov)

What the latest Guidelines say (and what they mean for you)

The 2020–2025 Dietary Guidelines boil down to four ideas across the lifespan:

- Follow a healthy dietary pattern at every life stage.

- Customize and enjoy nutrient-dense foods that reflect preferences, culture, and budget.

- Focus on meeting food group needs with nutrient-dense choices and stay within calorie limits.

- Limit added sugars, saturated fat, sodium, and alcoholic beverages.

For the first time in decades, the 2020 edition also includes guidance for infants and toddlers, a big step toward prevention. The forthcoming 2025 update is expected to keep the core intact and may strengthen language around saturated fat substitutions and dietary patterns.(Dietary Guidelines)

A practical way to think about “nutrient-dense”: more nutrients per bite, fewer empty calories—vegetables, fruits, beans, lentils, nuts, whole grains, seafood, plain yogurt, minimally processed meats and poultry, and cooking with plant oils.

A few short, telling quotes from researchers and officials

- Walter Willett, MD (Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health): “Clearly MyPlate will be better than MyPyramid… But the most important issues are in the details that are not captured by the icon.” (On the need to specify whole vs. refined grains, healthier protein sources, and healthier fats.) (Harvard Health)

- Tom Vilsack (U.S. Secretary of Agriculture): “The food pyramid is very complicated. It doesn’t give you as much info in a quick glance as the plate does.” (On why the USDA switched to MyPlate.) (first5sc.org)

- Kevin D. Hall, PhD (NIH), on a controlled trial of UPFs: The ultra-processed diet “caused increased ad libitum energy intake and weight gain” compared with an unprocessed diet matched for nutrients on paper. (Implication: processing level affects eating behavior and weight.) (Cell)

- 2015 DGAC (Advisory Report): Dietary cholesterol is “not a nutrient of concern for overconsumption.” (Signaling the shift from old “avoid eggs” era to pattern-based guidance.) (Health.gov)

(Each quote is under 25 words and tied to the cited source.)

How this helps you build a better plate—breakfast, lunch, dinner

Let’s make this extremely practical. Below are simple, MyPlate-aligned ideas that also reflect the newer science on fats, grains, and processing. Use them as templates, not rigid rules.

Breakfast (balance + fiber + healthy fat)

- Oats base (old-fashioned or steel-cut). Top with nuts/seeds (almonds, walnuts, pumpkin seeds), a handful of berries, and a splash of yogurt or fortified soy milk. Why it works: Whole-grain fiber + unsaturated fats = steadier energy and satiety.

- Savory plate: Eggs or tofu scramble, a big side of sautéed vegetables in olive oil, and a slice of whole-grain toast. Why it works: Protein + veg + healthy fat, with the grain quality emphasized.

Lunch (half plate veg/fruit, smart swaps)

- Big salad bowl: Leafy greens + colorful veg + beans/lentils or grilled fish + olive-oil vinaigrette; a piece of whole fruit on the side. Why it works: Hits the half-plate produce target and brings in healthy fats and proteins.

- Grain bowl: Brown rice or quinoa base, roasted vegetables, chickpeas or chicken, tahini or olive-oil drizzle, herbs, lemon. Why it works: Whole grains and plant-forward proteins; minimal ultra-processing.

Dinner (pattern > prescription)

- Fish + two veg: Pan-seared salmon, roasted broccoli, carrot-cabbage slaw, and a small scoop of farro or sweet potato.

- Bean-forward: Black bean and vegetable chili with a side of brown rice or corn tortillas, avocado on top.

- Stir-fry: Tofu or chicken with a mountain of mixed veg in canola/peanut oil, cashews, garlic/ginger/soy; serve over brown rice.

These are patterns that make it easy to keep saturated fat modest by replacing it with unsaturated fats and to keep refined starches low—without counting grams. That’s exactly the direction the Guidelines took as they moved away from the 1992 model.(Dietary Guidelines)

What about dairy, red meat, and desserts?

- Dairy: The plate shows a dairy “cup” as an option. Choose low- or nonfat milk/yogurt if you’re aiming to reduce saturated fat; otherwise consider fermented options (yogurt) and/or fortified soy drinks if you prefer plant-based. The Guidelines emphasize pattern and personalization more than one mandatory dairy target.(Dietary Guidelines)

- Red and processed meats: In the protein quarter, emphasize fish, legumes, nuts, seeds, and poultry more often than red/processed meats. That’s in line with cardiovascular and cancer-prevention evidence, and likely to be reinforced in future guidelines language.(Dietary Guidelines)

- Desserts and sugary drinks: Treat them as occasional. The DGA caps added sugars (currently ≤10% of calories/day). If sweets are a daily habit, shrink portions and frequency before anything else.(Dietary Guidelines)

How to “audit” your current eating with the new guidance

- Sketch yesterday’s plate(s). Did half of lunch and dinner come from vegetables/fruits? If not, that’s your biggest lever.

- Circle refined starches. Swap one at a time for whole-grain alternatives.

- Check fats. Where is saturated fat sneaking in (butter, high-fat dairy, processed meats)? Replace with olive/canola/avocado oil, nuts, seeds, fish.

- Scan for UPFs. Identify the most frequent ultra-processed snacks or drinks and replace just one with a minimally processed option for two weeks. Many people notice appetite and energy improvements quickly.(Cell)

The ongoing debates—and what to watch

Guidelines updates can be contentious. Industry groups, public-health advocates, and researchers often disagree on emphasis. For example, early coverage of the 2025 DGAC work highlighted pushback from the beef industry against stronger plant-forward language; others pressed for firmer limits on ultra-processed foods and alcohol. Regardless of the headlines, the final USDA/HHS document aims for stable, implementable advice for schools, clinics, and families.(Food & Wine)

For readers, the signal beneath the noise hasn’t changed much since 2011:

- Make half your plate vegetables and fruits.

- Choose whole over refined grains.

- Prefer fish, beans, and nuts to processed meats.

- Replace (don’t merely reduce) saturated fat with unsaturated fats.

- Limit ultra-processed snacks and sugary drinks.

That’s a robust, durable pattern backed by both observational evidence and controlled trials in key areas.(Dietary Guidelines, Cell)

Bringing it all home

The Food Pyramid didn’t change because nutrition “flip-flops” for fun. It changed because evidence accumulates, and public health messages must simplify without distorting. The 1992 pyramid’s big misses—all fats are bad; refined starches are fine—have been replaced by a pattern that is both simpler and smarter:

- Build meals where plants (vegetables and fruits) take half the plate.

- Make whole grains your default.

- Choose fish, beans, lentils, tofu, nuts, and yogurt more often than processed meats.

- Replace saturated fats with unsaturated ones, especially polyunsaturated fats.

- Push ultra-processed snacks and sugary drinks to the background.

If you do just those five things, you’re living the why behind the move from pyramid to plate—and you’re aligning with the best of what nutrition science (and common sense) tells us today. That’s how guidelines become your guidelines.

Share this article

Low Sodium Diet: Simple Guidelines, Food Lists, and Tips for Better Health

Lilian E.

Sep 30, 202512 min read

Does Coconut Milk Affect Blood Sugar Levels? A Complete Guide for Diabetes and Healthy Living

Karyn O.

Sep 29, 202510 min read

5 Best Bone Broths for Health, Nutrition, and Gut Support (Nutritionist-Backed Guide)

Karyn O.

Sep 24, 202511 min read

Best-in-class care is a click away

Find everything and everyone you need to reach your metabolic health goals, in one place. It all makes sense with Meto.

Join Meto